Salk Institute’s “Super” Plants Hope to Combat Climate Change

When Wolfgang Busch first became mesmerized by plant roots as a young scientist, he didn’t realize they could potentially help save the world. He was captivated by how, without a brain, they could do things like actively track down nutrients. Now, he believes the simple root—the unsung underground hero of foliage and flora everywhere—might just be the buffer between us and climate devastation.

Over billions of years, Busch explains, plants have evolved to take up carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air. They absorb it through their leaves, build their own biological material using the carbon, and then release the oxygen, which is the O2 that we breathe. In other words, every part of a plant has been constructed from CO2, powered by sunlight via photosynthesis. “Plants are very good at this,” he says. “So making them a little better will go a long way.”

For the past seven years, Busch and his team at The Salk Institute’s Harnessing Plants Initiative have been engineering plants to grow larger and deeper roots that also contain more suberin, a polymer found in the roots of all land plants that is legendary for sucking up carbon.

Busch says this recipe—deeper and more suberin-rich roots—will keep carbon locked beneath our feet for longer. Because suberin is slow to decompose (it’s like jawbreakers for soil microbes), it becomes “a very stable currency in the carbon bank of the soil,” he explains.

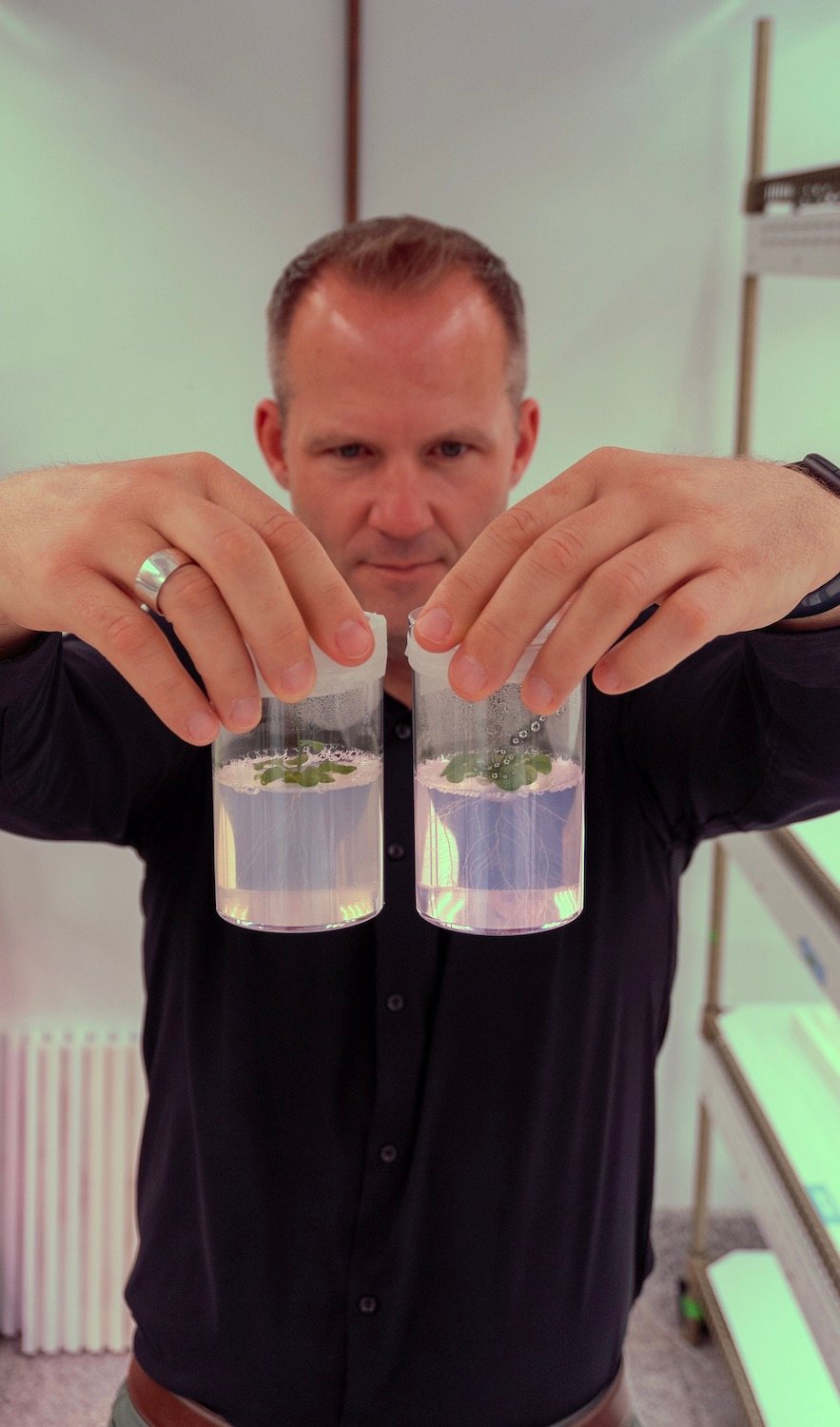

Busch shows off the new and improved root system of his “Salk Ideal Plants.”

Once Busch and his team master these magic roots on a model lab plant— and they are well on their way—they plan to transfer these traits to common crops to solve more than one problem: By the 2080s, the world population is expected to soar to 11 billion, and humanity will be growing more food to meet demand. “So combining food production with carbon sequestration was a no-brainer,” Busch says.

This is the masterplan: Farmers throughout the world adopt these “Salk Ideal Plants” as new growing specimens. As they feed Earth’s larger population, they will also be banking carbon beneath the sun drenched soil in a vast network of mega-roots. If everything goes to plan, Busch expects that in a couple of decades, his program will be responsible for pulling two gigatons of carbon out of the atmosphere each year, which would be equivalent to taking 400 million gasoline-powered cars off the road. “We just need to work very hard for it,” he says.

Larry the Seed-Planting Robot assists Busch and his team in the lab. Larry was specially engineered for the Salk Institute and paid for in part with a crowdfunding campaign.

Inside his lab, Busch picks up a small, translucent, cylindrical container with a tiny trial plant inside. The rice stalk is growing in clear agar gel, making its roots visible. The root system stretches downward like a mass of tributaries, small parts of something greater. “A lot of roots, huh?” Busch says, with a wide grin.

The post Salk Institute’s “Super” Plants Hope to Combat Climate Change appeared first on San Diego Magazine.

Categories

Recent Posts

GET MORE INFORMATION