San Diego-Based Leadership Coach Takes on Self-Talk in New Book

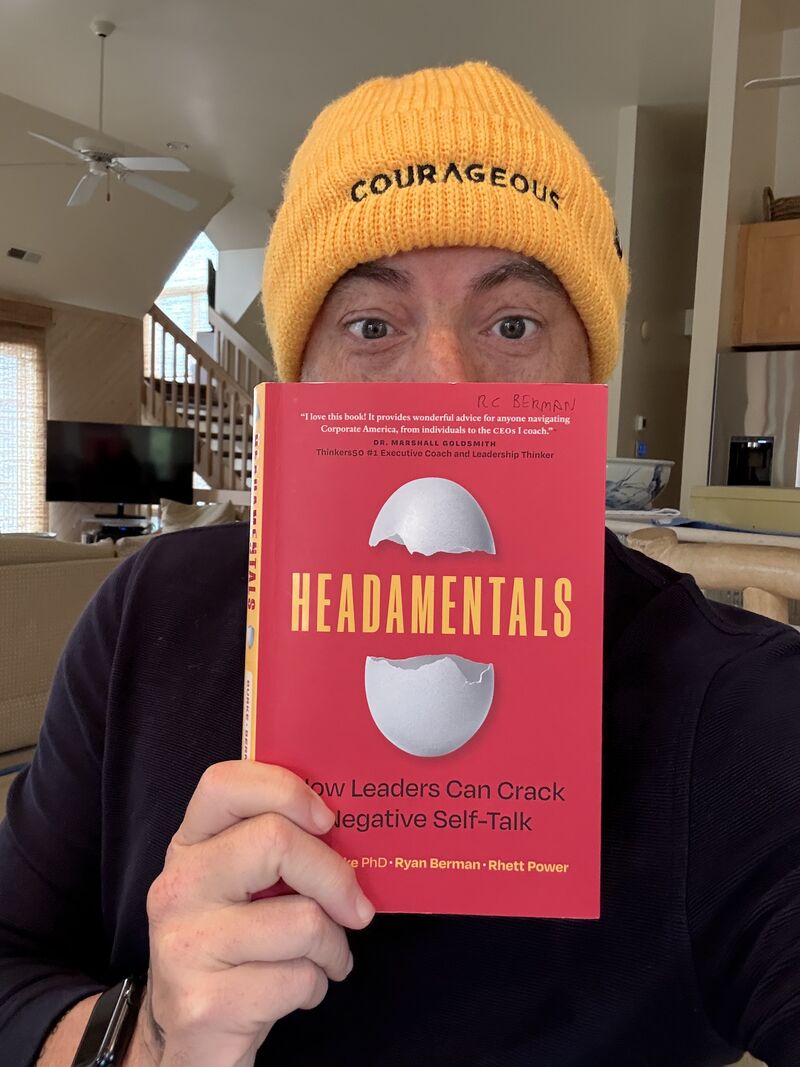

Ryan Berman describes himself as a “fear fighter.” The author, speaker, podcaster, and founder of the San Diego-based Courageous consultancy works to infuse courage into the DNA of companies across the country by identifying and combatting the fears that hold them back. Berman’s best-selling book R

17 Things to Do in San Diego This Weekend: November 12–16

It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas in San Diego. Winter Wonder at Belmont Park, SeaWorld’s Coastal Christmas, and Lightscape at San Diego Botanic Garden are all wonderful ways to get in the holiday spirit. Meanwhile, wine aficionados can get their fill at Uncorked: Derby Days at Del Mar Tho

San Diego Doctors Share Their Best Advice on Women’s Hormone Health

Everybody’s talking about hormones. Celebrities like Michelle Obama, Sex and the City’s Kim Cattrall, Oprah Winfrey, and the irrepressible Gwyneth Paltrow are waxing poetic on menopause, and, according to industry publication BeautyMatter, the market for products related to that particular life stag

Categories

Recent Posts